Fifteen to 20 percent of all Americans identify as neurodivergent. This number is comprised of 10 percent of people who are diagnosed with dyslexia, 6 percent with dyspraxia, 5 percent with ADHD and 1–2 percent with autism. Some studies suggest that nearly half of all Gen Z Americans identify as neurodivergent. And yet, most of our workplaces lack the educational resources, institutional practices and inclusive management coaching necessary to help meet different neurodiversity needs.

What is neurodiversity?

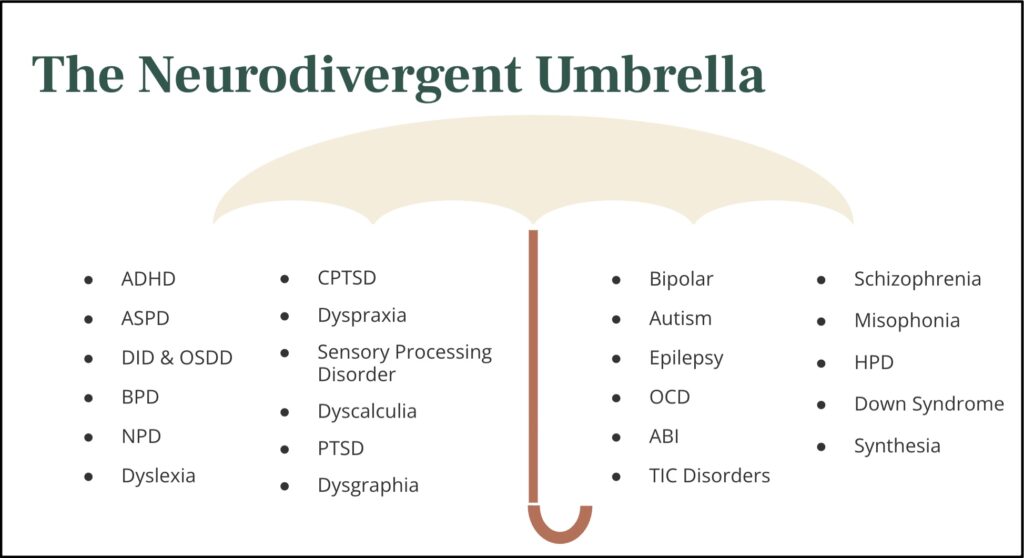

The term neurodiversity, originally coined by Judy Singer in 1997, refers to the natural diversity of human brains. A neurodivergent person is someone whose brains works differently than what society deems “normal.” So, what is normal?

“Normal” or “typical” brain function means is determined by cultural context, social relationships, environmental factors and even other people’s perceptions. As the neurodiversity movement promotes social justice for people within its wide umbrella, the types of diagnoses and conditions considered under the neurodiversity umbrella has grown and will likely continue as our collective understanding of the human brain evolves.

3 advocacy strategies

Rigid schedules, an overemphasis on written communication and an abundance of ambiguous rules and policies around what traumatic content can and cannot be shared, are just a few examples of standard workplace practices that disproportionately impact folks who identify with one or more of the categories under the umbrella. As a talent leader, here is what you can do to advocate for your neurodivergent employees.

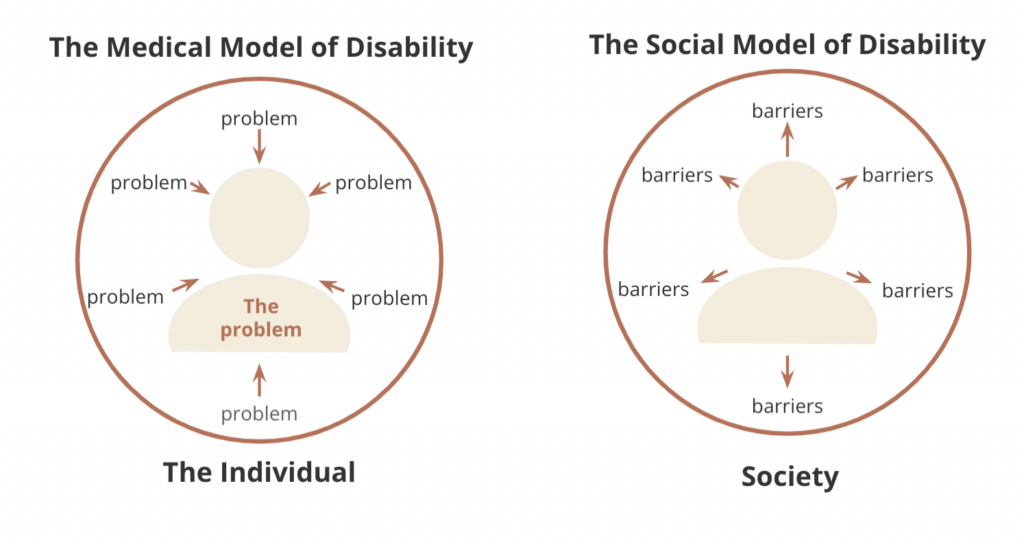

1. Remove barriers rather than spotlight individual issues

The medical model of disability suggests that problems originate with the neurodivergent person and their “atypicality,” which leads to shaming, blaming and silencing employees who would otherwise request accommodations. Frame the conversation in terms of the social model, which looks outward at the barriers that exist for neurodivergent people, rather than what about them needs to change.

If you wouldn’t tell a wheelchair user to “stop using their wheelchair,” then don’t tell someone with dyslexia to “stop struggling to read.” In that situation, ask whether information can be presented differently, verbally, in slides, or in another form that better aligns with an employee’s strengths and assets.

2. Proactively offer reasonable accommodations

The reality is that most people who need accommodations don’t even know what they are, let alone which are available to them. Create a clear list of neurodiversity-specific accommodations to circulate across your organization, always leaving room for folks to request others not listed. Here’s a starting point.

| Category | Accommodation |

|---|---|

| Speech | – Provide alternative ways of communicating (writing, demonstrations, etc.) – Provide text-to-speech assistive technologies – Set meeting norms with team members to allow for pauses and breaks between verbal exchanges to allow non-speaking participants to contribute in other forms |

| Listening comprehension | – Provide brief notes in writing for any information conveyed auditorily – Provide interpreter, transcription, and/or captioning services |

| Reading | – If there are any written documents during meetings, presentations or other demonstrations, provide alternate options (large print, Braille, electronic, tape-recorded, etc.) – Provide verbal instructions |

| Additional | – Allow attendants or support people to attend meetings or team functions when necessary for the employee to participate – Allow participants to disclose their preferred working time – Plan for longer meeting times if needed |

3. Avoid pathologizing neurodiversity

In everyday conversations, you may notice employees have a tendency to use the words for diagnoses as short-hand for negative behaviors. For example, an employee complaining about a colleague paying too much attention to formatting issues could describe the detail-oriented peer as being “so OCD” or a manager might say they don’t want to give a teammate feedback because whose emotional responses to critique are unpredictable as “bipolar.”

By using these phrases, the message to folks who really do live with OCD or bipolar disorder is that their behaviors are undesirable and “wrong.” When in doubt, always describe exactly what you mean rather than using linguistic shortcuts. Help others do the same.

Parting words

Even though so many workers are neurodivergent, our workplaces aren’t designed to support their needs. The result is overtired, overwhelmed and overburdened employees who can’t access a true feeling of belonging on their teams. With a few simple practices, you can improve the employee experience while unlocking the natural gifts and strengths of the people who make up your organization.